“It’s gonna be a long, hot summer!"

In the wee hours of Sunday, July 23, 1967 in the Virginia Park neighborhood on Detroit’s west side, the predominantly Black community unbeknownst to all was at a precipice and had a revolutionary and cataclysmic response of epic proportions when police broke up a party celebrating the return of soldiers from the Vietnam War at a blind pig (an illegal bar) at the corner of 12th St (now Rosa Parks Boulevard) and Clairmont. Now the events that followed as to what sparked the raid to a full-blown riot are unclear. By most accounts and prior to the rebellion, the community was terrorized by a group of officers known as the “Big Four” (four white officers of the Detroit Police Department), systemic and institutional injustices were commonplace and imposed illegal housing laws obligated Blacks to live west of Woodward Avenue (a main thoroughfare). One of the most significant contributors to the uprising was housing by way of the highways and interstates that ran through majority Black neighborhoods (Black Bottom, Paradise Valley and Conant Gardens) uprooting scores from densely packed housing to another with no relief in sight. Detroit, Motown, the “D” captivated waves of disenfranchised Blacks from the south to the city on the promise of paying five dollars a day working in the automobile plants. Motown is home to thousands of direct migrants of the Great Migration (1915-1970) and thousands more descendant’s kin.

Sunday, the first day of the Detroit Riots, also known as “the Great Rebellion” and the days to follow Detroit mirrored the violence American men and boys faced overseas in Vietnam—fires, sniping, looting, rioting and a racially motivated bloodbath at the Algiers Motel. “Transporting those from the blind pig took so long the mood of the crowd drastically changed, said former Police Commissioner Ray Girardin in an oral history interview.”[1] In an oral history conducted by deceased esteemed historian and scholar Sidney Fine interviews retired Civil Rights Commissioner and Housing Commissioner Judge Damon Keith, “On the 24th [the second day] it became bigger than the police, National Guard, the State Police and the troopers were called in. July 24th was the worse day of the riot the most death, most destruction, most fires.”[2]

As Fine’s oral history interviews revealed, when the federal troops were called in a divide between the National Guard and the Army crippled response time and crisis management in what could be interpreted as a power/ego trip. Former Governor George Romney says the Army made their headquarters east of Woodward. Likewise, many of the Army officers on city streets were Black, and as one could imagine returned from Vietnam war-torn. Similarly, the National Guard set up command west of Woodward Avenue.[3]

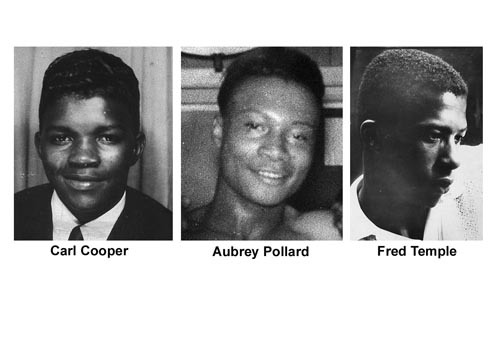

In the midst of the chaos there was a racially motivated bloodbath at the Algiers Motel off of Woodward Avenue, in which police officers and/or national guardsmen killed three black men and brutally assaulted roughly seven others including three white women. There are variations as to the storyline of what occurred that led to the officers being tried in an Ingham County court, and eventually being exonerated of the charges brought against them. [4] Former Detroit News journalist John Hersey wrote a compelling account of what happened in The Algiers Motel Incident.

In the midst of the chaos there was a racially motivated bloodbath at the Algiers Motel off of Woodward Avenue, in which police officers and/or national guardsmen killed three black men and brutally assaulted roughly seven others including three white women. There are variations as to the storyline of what occurred that led to the officers being tried in an Ingham County court, and eventually being exonerated of the charges brought against them. [4] Former Detroit News journalist John Hersey wrote a compelling account of what happened in The Algiers Motel Incident.

During the long, hot summer of 1967 more than 100 cities went up in flames. The following year, roughly the same cities would once again erupt in violence as an emotional response to the assassination to Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Lee Sustar argues that we should examine uprisings from the perspective of the working class.

Panicked politicians denounced the “rioters” in thinly veiled—or not so-thinly-veiled-racial terms. The governor sends in the National Guard to repress the uprising with overwhelming force…Detroit, the center of the U.S. auto industry—exploded in response to police violence.[5]

Moreover, the Kerner Commission found,

the typical rioter was a teenager or young adult, a lifelong resident of the city in which he rioted, a high school dropout; he was, nevertheless, somewhat better educated than his non-rioting Negro neighbor, and was usually underemployed or employed in a menial job. He was proud of his race, extremely hostile to both whites and middle-class Negroes and, although informed about politics, highly distrustful of the political system.[6]

Lastly, Sustar, posits that the rebellions were “successful in wresting concessions from local, state and federal authorities—such as pullback from aggressive policing or greater spending on social services. He masterfully articulates that this is “collective bargaining by riot.”[7] As it pertains to Detroit, this can be debated whether “collective bargaining by riot” was impactful, because many who live there post-1967, have said the concessions that were gained were at the very best, minimal, if that.

The four-day rebellion was by far the most devastating on record of the 20th century until the 1992 L.A. riots following the Rodney King verdict. As expected, there’s conflicting information as to the loss and damages. Forty-three people died—at least that was what was reported, there’s a belief that there were more fatalities. The riots by the numbers: more than 2,000 people were injured; over 7,000 people filled the jails in the city and the overflow on Belle Isle ("Belecatraz"), the state penitentiary in Jackson and the federal prison in Milan; city firefighters either put out, watched or ignored the calls for roughly 2,000 building fires and millions were reported in damages.[8] Police Commissioner Girardin asserts that when it came to the organization of the uprising that he believes it wasn’t planned. “This was not a conspiracy. This is a spontaneous situation.”[9] Most importantly, Girardin makes two powerful statements that address the gravity of the situation, “…it wasn’t a race riot like ’43 when the blacks and whites were fighting.”[10] And, “…this was a revolution, a riot by black people over the system.”[11]

The four-day rebellion was by far the most devastating on record of the 20th century until the 1992 L.A. riots following the Rodney King verdict. As expected, there’s conflicting information as to the loss and damages. Forty-three people died—at least that was what was reported, there’s a belief that there were more fatalities. The riots by the numbers: more than 2,000 people were injured; over 7,000 people filled the jails in the city and the overflow on Belle Isle ("Belecatraz"), the state penitentiary in Jackson and the federal prison in Milan; city firefighters either put out, watched or ignored the calls for roughly 2,000 building fires and millions were reported in damages.[8] Police Commissioner Girardin asserts that when it came to the organization of the uprising that he believes it wasn’t planned. “This was not a conspiracy. This is a spontaneous situation.”[9] Most importantly, Girardin makes two powerful statements that address the gravity of the situation, “…it wasn’t a race riot like ’43 when the blacks and whites were fighting.”[10] And, “…this was a revolution, a riot by black people over the system.”[11]

The paradox of this leaderless uprising and the violence to follow in 1968 after Dr. King’s death it drastically shifted the demographics, economics and politics of the city, reinforcing white flight to the suburbs, black flight to other urban centers and ironically black resistance to stay put and rebuild. Unlike most American cities, the rebellion tore the city apart and led to the slow and painful decades long demise and deterioration for the country to see, a city lost to the false promises of rebirth, growth, urban renewal and globalization. Unsurprisingly, much to the chagrin of public leaders lived up to James Baldwin’s adage, “Urban renewal is negro removal.”

[1] Ray Girardin, 1 of 3, #3264, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

[2] Detroit Riot Oral History, 21 June 1985, Sidney Fine Collection—Judge Damon Keith, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[3] Detroit Riot Oral History, 21 June 1985, Sidney Fine Collection—Gov. George Romney, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

Detroit Riot Oral History, 21 June 1985, Sidney Fine Collection—Judge Damon Keith, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[4] The Michigan Chronicle

John Hersey, The Algiers Motel Incident (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1997).

[5] Lee Sustar, “Riots, Rebellions and the Black Working Class, SocialistWorker, May 6, 2015, accessed December 1, 2015 http://socialistworker.org/2015/05/06/rebellion-and-the-black-working-class

[6] Ibid.,

[7] Ibid.,

[8] “The Riot,” Detroit Free Press (Detroit, Michigan), July 27, 1967.

John Hersey, The Algiers Motel Incident (New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1968), 53.

[9] Ray Girardin, 1 of 3, #3264, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

[10] Ibid.,

[11] Ibid.,